Intro to Build Systems

What is a Build System?

We can think of build systems as a set of tools, programs, scripts, and methods to consistently and correctly produce the required build artifacts (application binaries, system configuration files, test results, etc).

Given the integration of IDEs and extensible text editors, you would not be blamed for not considering these details. Most development tools are designed to hide these details from the user for ease of us. However, the truth is you've probably been using or have encountered build systems without realizing it. For the curious, take you might want to take a look at the Arduino Sketch Build Process .

High-Level View

Before getting into the technical details, benefits, and rationale behind implementing build-systems, we should take a look at the bigger picture.

For most projects in the embedded software space, the code must be compiled to a architecture specific binary/image/executable that is loaded to a specific target. But there are a surprising amount of steps that go into getting those artifiacts. We won't cover the technical details of how compilers and toolchains work but we should note that there are a few core steps involved with this process including but not limited too:

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Compiling | The process of converting human-readable code into machine code relative to the target architecture |

| Linking | A combining/connection all compiled artifacts into an executable file |

| Assembling | The act of converting assembly code into machine code |

For a more thorough overview on the build & compilation processes, watch this video.

Even for something as small as turning on an LED has many considerations need to be made when we look at the building process. For the most part, we can break down this process into two categories/scenarios:

- Manually compiling code using GCC (or another toolchain)

- Using an external tool/interface to configure compiler options

Scenario 1. Manually compling:

For small projects that only have a single developer and a few source files, this is easy to manage. There are only a few commands and arguments you need to pass to your toolchain.

For reference, consider the classic hello world example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello World :) "\n);

}

gcc main.c -o helloWorld

> ./helloWorld

> Hello World :)

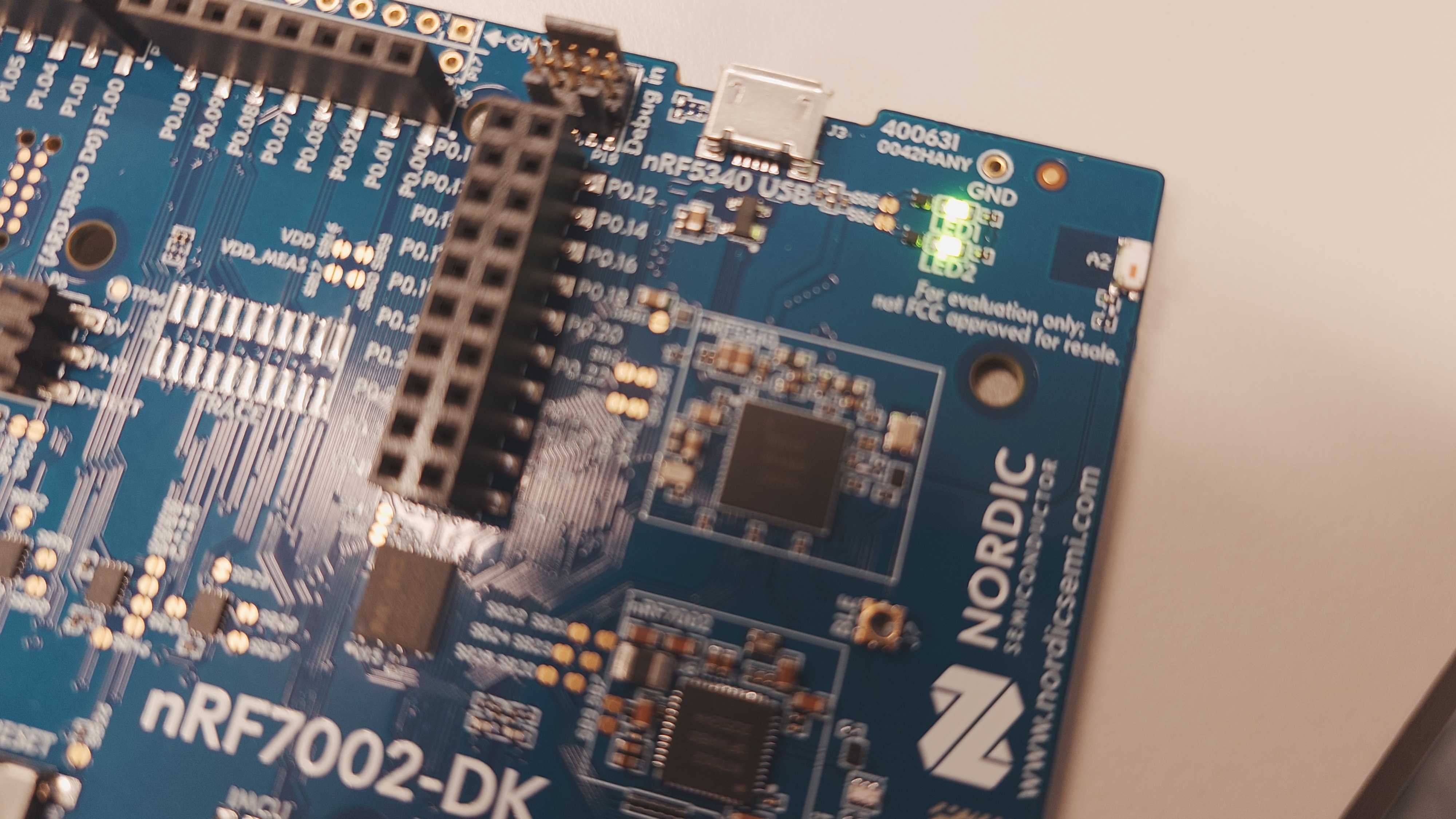

Seems easy enough right? Well let's up the anty. Let's say you're trying to compile some embedded code to turn on an LED for a Nordic nrf5340 MCU. Your setup might look like this now:

/*******************************************************************

* File: turnOnLEDs.c

*

* Author: Miles Osborne

*

* Purpose: Application source for turning on both onboard LEDs of the

* nRF7002DK development board

***********************************************************************/

#include "nrfx.h"

#include "nrf_gpio.h"

/*******************************************************************

* Function: main

*

* Purpose: Application entry point

*********************************************************************/

int main(void) {

/*******************************************************

* Set P1.06 (LED1) to output and write a logical 1 to

* the pin to turn on the LED

********************************************************/

NRF_P1->PIN_CNF[6] |= 1;

NRF_P1->PIN_CNF[6] |= 1<<1;

NRF_P1->DIR |= GPIO_DIR_PIN6_OUTPUT<<GPIO_DIR_PIN6_POS;

NRF_P1->OUTSET |= 1 << GPIO_OUTSET_PIN6_POS;

/*******************************************************

* Set P1.07 (LED2) to output and write a logical 1 to

* the pin to turn on the LED

********************************************************/

NRF_P1->PIN_CNF[7] |= 1;

NRF_P1->PIN_CNF[7] |= 1<<1;

NRF_P1->DIR |= GPIO_DIR_PIN7_OUTPUT<<GPIO_DIR_PIN7_POS;

NRF_P1->OUTSET |= 1 << GPIO_OUTSET_PIN7_POS;

while(1);

return 0;

}

arm-none-eabi-gcc -mcpu=cortex-m3 -mfloat-abi=soft -O1 -I ../Include -D CORE_HEADER="core_cm3.h" -c -D __CM3_REV=0x0000U -D __MPU_PRESENT=1U -D __VTOR_PRESENT=1U -D __NVIC_PRIO_BITS=3U -D __Vendor_SysTickConfig=0U -o ./src/Output/apsr.c.o ./src/apsr.c; llvm-objdump --mcpu=cortex-m3 -d ./src/Output/ apsr.c.o | FileCheck --allow-unused-prefixes --check-prefixes CHECK,CHECK-THUMB ./src/apsr.c ...

Note

Source code aside, there are significantly more settings and compilation flags to worry about right? That comes with the territory of complex projects but having to manually type out these commands each time would get tiring very quickly. Also consider that a simple typo might lead to an incorrect output or resulting binary.

In general, as a project gets larger and more complex, it becomes harder to maintian. What if you add new developers to the team? How do you ensure that all your builds are exactly the same? What if they added additional compiler flags between commits that (accidently) changed the target architecture without you knowing? How would you go about setting up testing builds or simulator builds? It would be pretty painful to have to manually add all the arguments each time for projects that are comprised of thousands of lines of code and hundreds of files across multiple subsystems.

Scenario 2. Using an External Tool

In fairness, some of these problems mentioned above can be resolved by ensuring good communication between team memebers which is always a good thing. But instead of having to verbally commmunicate each change and checking over everyone's shoulder to ensure the build is correct, we can effectively automate that process and ensure that every machine that runs the same command will get the same output.

As a start, let's consider the make tool and corresponding makefiles.

CC = arm-none-eabi-gcc

OBJCOPY = arm-none-eabi-objcopy

CFLAGS = -mcpu=cortex-m33 -mthumb -std=gnu11 -Wall -O2 -g -DNRF5340_XXAA

LDFLAGS = -Tnrf5340.ld -nostartfiles -L. -lm

# Directories

SRC_DIR = src

BUILD_DIR = build

# Files

TARGET = turnOnLEDs

SRC_FILES = $(SRC_DIR)/turnOnLEDs.c

OBJ_FILES = $(SRC_FILES:$(SRC_DIR)/%.c=$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o)

# Rules

all: $(TARGET).bin

$(TARGET).elf: $(OBJ_FILES)

$(CC) $(OBJ_FILES) $(LDFLAGS) -o $(BUILD_DIR)/$@

$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o: $(SRC_DIR)/%.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

$(TARGET).bin: $(TARGET).elf

$(OBJCOPY) -O binary $(BUILD_DIR)/$< $(TARGET).bin

clean:

rm -rf $(BUILD_DIR) $(TARGET).bin $(TARGET).elf

The source code remains the same but instead of manually specifying compiler options and parameters from the command line, you develop a makefile which lists how you want your program to be compiled and linked. It is also worth noting how much easier this is to read and maintain when compared to a long string of command line arguments.

Note

If you're interested in learning more about make and makefiles, you should consider giving the following resources a look:

Why We Should Care about Build Systems

What's the takeaway here? Build systems are not a silver bullet. They will not magically make your application/program/project start working (usually). However, as engineers, not only should we be concerned with what we're doing but how we're doing it. Build systems are a tool to help make development easier, more reliable, and consistent across developers and development teams.

Below are a few reasons or experiences that may convince you to consider learning and or integrating build systems into your next project.

1. Inconsistent Builds

- The timeless "it works on my machine"

- Increased likelihood of hidden bugs

- Missing dependencies are almost guaranteed

- Your application might not even compile :(

2. Brittle Development

- Parts of the project tend to break with the slightest breeze!

- Testing process is not standardized or automated

- Broken code can be committed without being noticed

- Hardware may even be required for testing logical parts of the code

3. "Artisanal" Development

- More of a style convention that build systems helps influence

- Code is not modular.

- Too many dependencies in the main codebase

- Hard to reuse code across multiple projects

- Leads to re-inventing the wheel

4. Slow Bring-up Time

- It takes time to get up to speed with new projects especially for new developers

- It is extremely to get demoralized from a project that fights you at every action.

- See If They Come, How Will They Build It?

More Developer Woes

- BTW This is only the tip of the iceberg :)

While we are mostly focusing on CMake, there are many options for build systems which includes but is not limited to:

| Build System | Description |

|---|---|

| Meson | "Meson is an open source build system meant to be both extremely fast, and, even more importantly, as user friendly as possible. The main design point of Meson is that every moment a developer spends writing or debugging build definitions is a second wasted. So is every second spent waiting for the build system to actually start compiling code." |

| Bazel | "Bazel is an open-source build and test tool similar to Make, Maven, and Gradle. It uses a human-readable, high-level build language. Bazel supports projects in multiple languages and builds outputs for multiple platforms. Bazel supports large codebases across multiple repositories, and large numbers of users." |

| Make | "GNU Make is a tool which controls the generation of executables and other non-source files of a program from the program's source files. Make gets its knowledge of how to build your program from a file called the makefile, which lists each of the non-source files and how to compute it from other files" |

For embedded software, a lot of care must be taken to ensure application binaries are consistent between developers especially for large/complex projects with multiple developers.

NOTE: Build systems are not exclusive to embedded systems and low-level languages (i.e C/C++) they are very prominent in this space.